An excellent summary of what we do and don't know about the "Big Bang,"

and why there currently is no other model for the origin of our universe

that offers a serious alternative. The premise that many of the

objections to this model are based on misunderstanding it is well proven

by quite a few of the initial posts. This is why I would suggest fully

reading an article before responding to it, rather than posting a

response which clearly is a reaction to the headline.

"At the same time, it is important to be open about how much we don’t know. It is not only possible, it is absolutely certain that our understanding of the Big Bang is incomplete."

Could the Big Bang Be Wrong?

The Big Bang is the defining narrative of modern cosmology: a bold

declaration that our universe had a beginning and has a finite age, just

like the humans who live within it. That finite age, in turn, is

defined by the evidence that universe is expanding (again, and

unfortunately, many of us are familiar with that feeling as well). Those

two ideas–a singular cosmic beginning, followed by billions of years of

cosmic growth–are so strange that some people have never made peace

with them. As a result, skeptics have been questioning the validity of

the Big Bang model for as long as there has been a Big Bang model.

Among

mainstream cosmologists, doubts about the Big Bang largely melted away

in the 1960s with the discovery of the cosmic microwave background–an

omnidirectional buzz of radiation that makes sense only as a relic from

the hot, early era of the universe. But around the fringe, the doubts

have persisted. Lately they have intensified, inspired by a puzzling discrepancy

in different measurements of how the universe is expanding. Even

scientific centrists acknowledge that our understanding of the early

universe is glaringly incomplete. So now is a prime time, it seems to

me, to dig into the big question: Could the Big Bang be wrong?

This

question comes up all the time in public forums and on social media. In

most cases, it seems rooted not so much in misgivings about the science

as in misunderstanding of what the science is. Any meaningful answer

therefore has to begin with a crucial piece of clarification: The Big Bang means two quite different things depending on who you are talking to.

In

popular conversation, the Big Bang is often used broadly to mean the

mysterious primal event that created the universe, and it is commonly

envisioned as a tremendous explosion emanating from a single point. (To

be fair, popular articles and illustrations often reinforce those ideas

with oversimplification and confusing language.) But that is not what

cosmologists mean by the Big Bang.

One key point is that the Big Bang was not an explosion of the kind any person has ever witnessed. “This is a hard concept for people to get their heads around,” says Wendy Freedman,

a veteran cosmologist at the University of Chicago. “The first thing to

get rid of is an image analogous to a bomb — which is our first

tendency to imagine, and which is wrong — where you have an explosion

with matter that flies outward from a center. This is not what happens

in space. The Big Bang is an explosion of space, and not into space. There is no center or edge to the explosion.”

There

was no place outside of the Big Bang, so it was not expanding into

anything. Rather, all of space began expanding, everywhere. That is why

galaxies appear to be moving away from us in every direction. Any

observer, anywhere, would see the same thing. I sometimes think of the

Big Bang as a metaphor for human psychology. In a sense, you can think

of yourself as the center of the universe, since that’s how it looks to

all observers. But in a deeper sense, nobody is at the center, since the

expansion is everywhere and all of us are in the same situation.

For

anyone wondering how the universe could have formed from an explosion

at one point in space, the answer is that it couldn’t. That idea truly

is wrong — but it is also not at all what the Big Bang describes.

Which brings me to the other key point: The Big Bang is a description of how the universe began, not an explanation of why

it began. It does not assume anything about what (or who) made the

universe, and it does not assume anything about what (if anything) came

before.

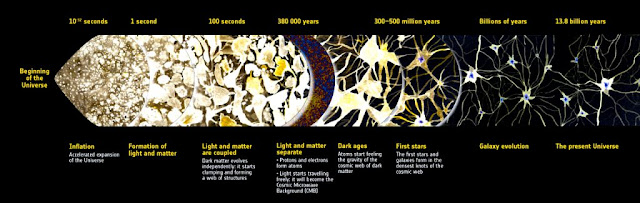

To modern cosmologists, the Big Bang is a model describing how

the universe expanded from an extremely hot, dense early state into the

reality that we see today. The evidence for this interpretation

overwhelming. Certainly, nothing else has come anywhere close in the

last 50 years, even as our knowledge about the universe has grown

tremendously.

The most famous evidence for the Big Bang comes from

“redshifts,” the observed stretching of light from distant galaxies,

but that’s hardly the only source of support. The spectrum and

distribution of the cosmic microwave background exactly matches

expectations of the hot Big Bang. The evolution of galaxies testifies to

the finite age of the universe, and the observed ages of stars exactly

match up with the age of the universe deduced from the cosmic expansion.

The large-scale distribution of galaxies displays a subtle rippling

pattern that corresponds to the inferred rippling of acoustic waves in

Big Bang’s primordial soup of particles and radiation. The observed

abundances of hydrogen, helium, deuterium and lithium in the universe

exactly align with models of the nuclear reactions that occurred in that

soup.

Could that entire Big Bang framework of interpretation be wrong? I wouldn’t say it’s impossible, but I will call it … inconceivable.

One

of the last serious holdouts against the Big Bang was late cosmologist

Geoffrey Burbidge, who had championed the Steady State cosmology early

in his career and refused to abandon his pet theory even long after the

evidence falsified it. Later in life he came up with a complicated

oscillating-universe model, which effectively incorporates many small

big bangs. So really, he accepted the Big Bang, just without saying so. Discover ran a detailed profile of Burbidge and his ideas in 2005.

I’ve come across many proposed alternatives to the Big Bang, but I’ve

never seen one that deals honestly and comprehensively with the vast

observational evidence that our universe had a hot, dense beginning

about 13.8 billion years ago. The closest to a true outsider alternative

that I know of is the plasma-cosmology model of Eric Lerner, a plasma

physicist who developed a cult following for his view that the Big Bang

never happened. His model is thoroughly inconsistent with the data, however.

At the same time, it is important to be open about how much we don’t know. It is not only possible, it is absolutely certain that our understanding of the Big Bang is incomplete.

Cosmic

inflation is a widely accepted theory about what happened during the

first fraction of a second during the Big Bang, but it is not proven.

The current dispute over the cosmic expansion rate may be a reflection

of our ignorance about that early era. Why and how the Big Bang occurred

are complete mysteries. You may have heard cosmologists speculate about

the “multiverse,” or about the idea of an oscillating universe with

many beginnings, or about a collision between two membranes of reality

that created our universe. Nobody knows which of these ideas, if any, is

correct. But what they all have in common is that they all accept the

evidence that our current universe emerged from an intensely hot, dense

early state — which is to say, they all take the Big Bang as their

starting point.

Was there a time before the Big Bang? Will the

universe expand forever? Will there be another Big Bang? Is the universe

finite or infinite? Do other universes exist? These are all exciting,

wide open questions. We have a lot to learn about our place in nature’s

grand scheme. But we can be quite confident that, wherever future

theories and discoveries take us, the Big Bang will be a part of the

picture.

No comments:

Post a Comment