Latin

America’s most celebrated heroes came from vastly different political

traditions. What bound them together was not ideology, but a shared

insistence on defending the interests of their people – and, above all,

national sovereignty. In the 19th century, that struggle was directed

against European colonial powers, primarily Spain. By the 20th, it

increasingly meant confronting pressure from the United States, which

since at least the late 1800s had openly framed the region – codified in

doctrines and policy – as its strategic “backyard.

Those

who chose accommodation over resistance left a far murkier legacy.

Under intense external pressure, many leaders accepted limits on

sovereignty in exchange for stability, investment, or political

survival. Over time, this produced a familiar historical pattern:

figures who aligned with foreign power were readily replaced when they

ceased to be useful, while those who resisted – often at great personal

cost – were absorbed into national memory as symbols of dignity,

defiance, and unfinished struggle.

In this piece, we revisit the

heroes and the betrayers who came to embody these opposing paths in

Latin America’s modern history.

National heroes

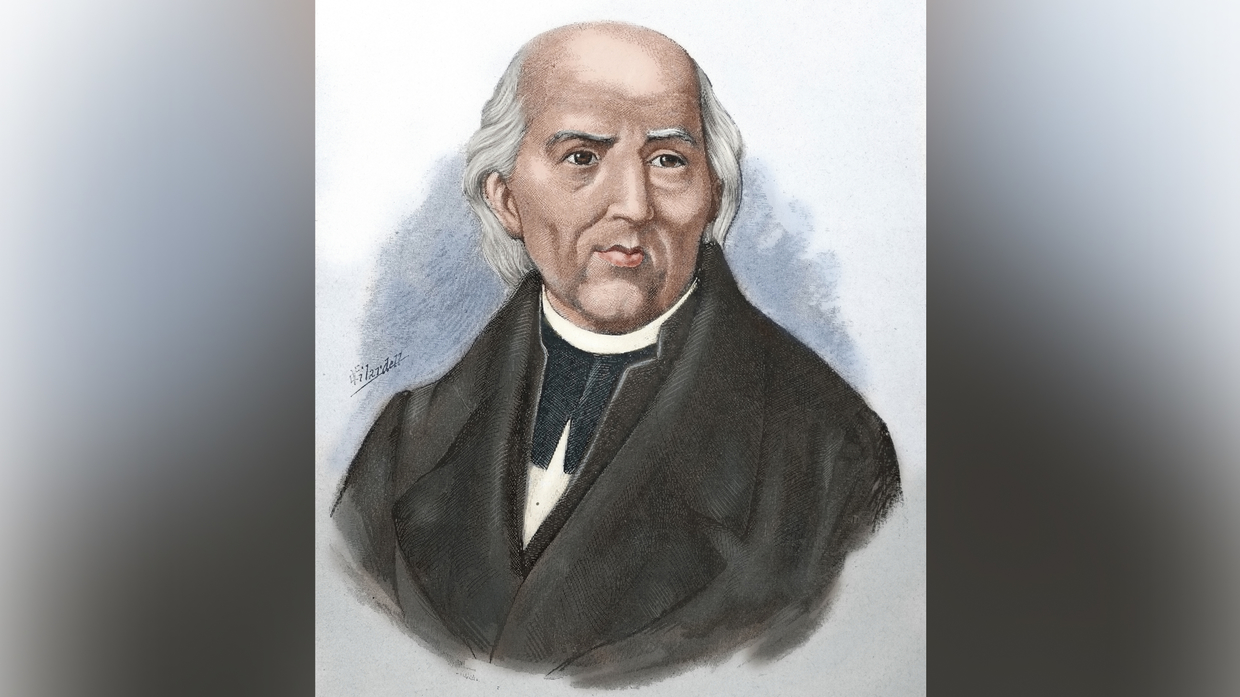

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla (1753–1811)

was a Mexican Catholic priest who entered history as the initiator of

Mexico’s war of independence from Spanish rule. On September 16, 1810,

he delivered the famous Grito de Dolores, calling on the people to rise

up – an act that later earned him the title “Father of the Nation” (Padre de la Patria).

Hidalgo led an insurgent army, won a series of early victories, and

issued decrees abolishing slavery, ending the poll tax, and returning

land to Indigenous communities. Captured in 1811, he was executed by

firing squad. His name lives on in cities, the state of Hidalgo, an

international airport, an asteroid, and on Mexico’s 1,000-peso banknote.

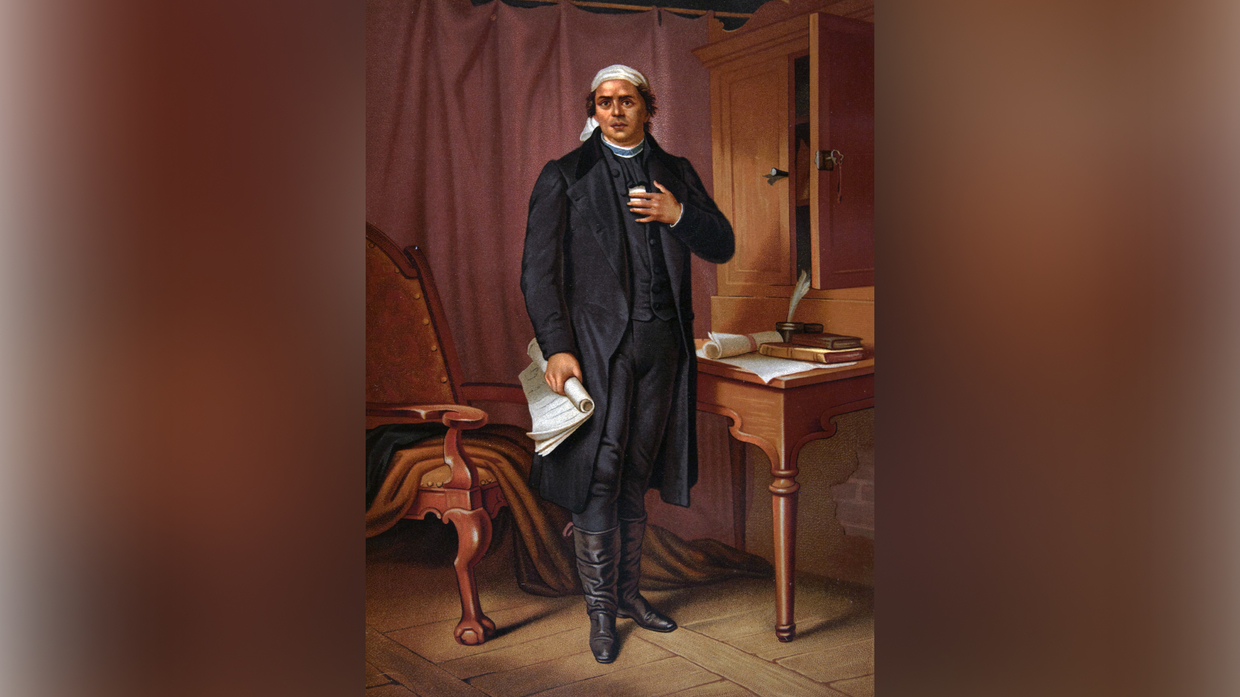

José María Morelos (1765–1815)

was a Mexican national hero who played a decisive role in the struggle

for independence from Spanish colonial rule. After Miguel Hidalgo’s

death, Morelos took command of the rebel forces, secured several major

military victories, convened a National Congress, and presented a

sweeping program of political and socio-economic reforms known as

Sentiments of the Nation. The document called for the abolition of

slavery and racial discrimination, the establishment of popular

sovereignty, and guarantees of fundamental civil rights. Though defeated

and executed in 1815, his ideas and personal sacrifice helped sustain

the independence movement.

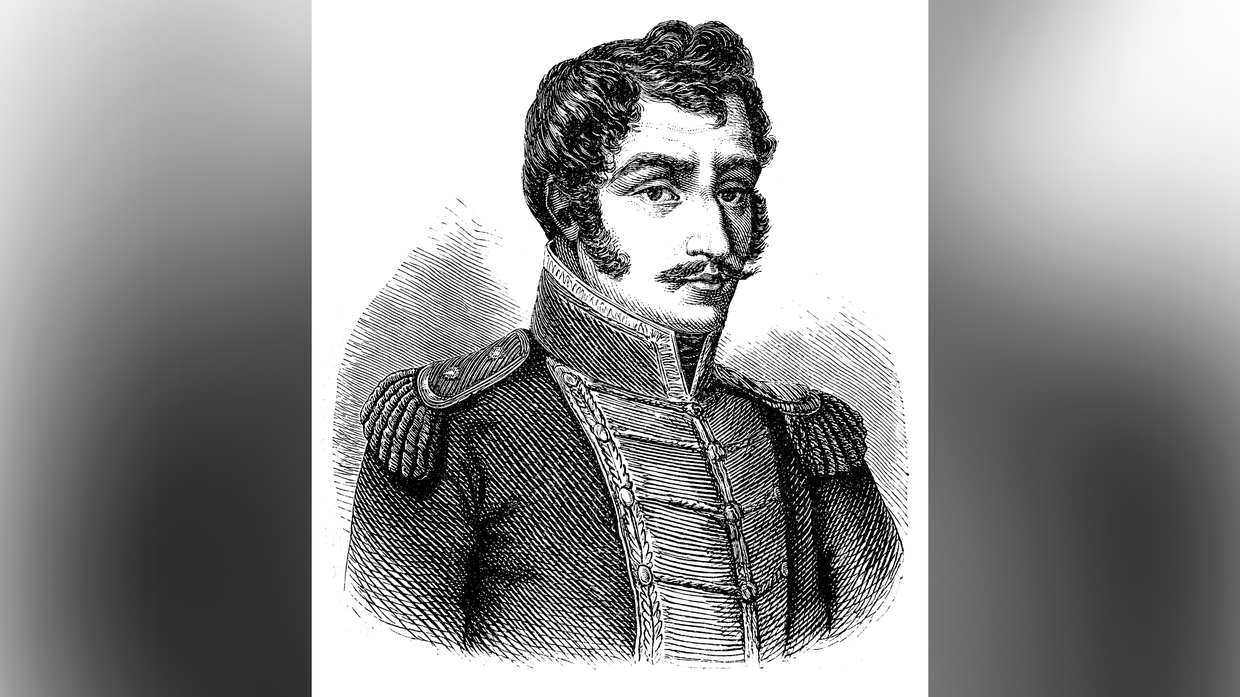

Simón Bolívar (1783–1830)

was a Venezuelan revolutionary and a national hero not only in

Venezuela but across much of the region. Known as El Libertador, he

played a central role in freeing the territories of present-day

Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia – named in his honor –

from Spanish rule. Bolívar promoted the abolition of slavery and the

redistribution of land to soldiers who fought in the wars of

independence. His lifelong ambition was the creation of a unified South

American state.

José de San Martín (1778–1850)

was one of the principal leaders of the Latin American wars of

independence against Spain and is revered as a national hero in

Argentina, Chile, and Peru. He was instrumental in liberating these

countries from colonial rule and in abolishing slavery. His legacy is

preserved in monuments, street names, schools, and public institutions.

In Argentina, he is honored as the Father of the Nation.

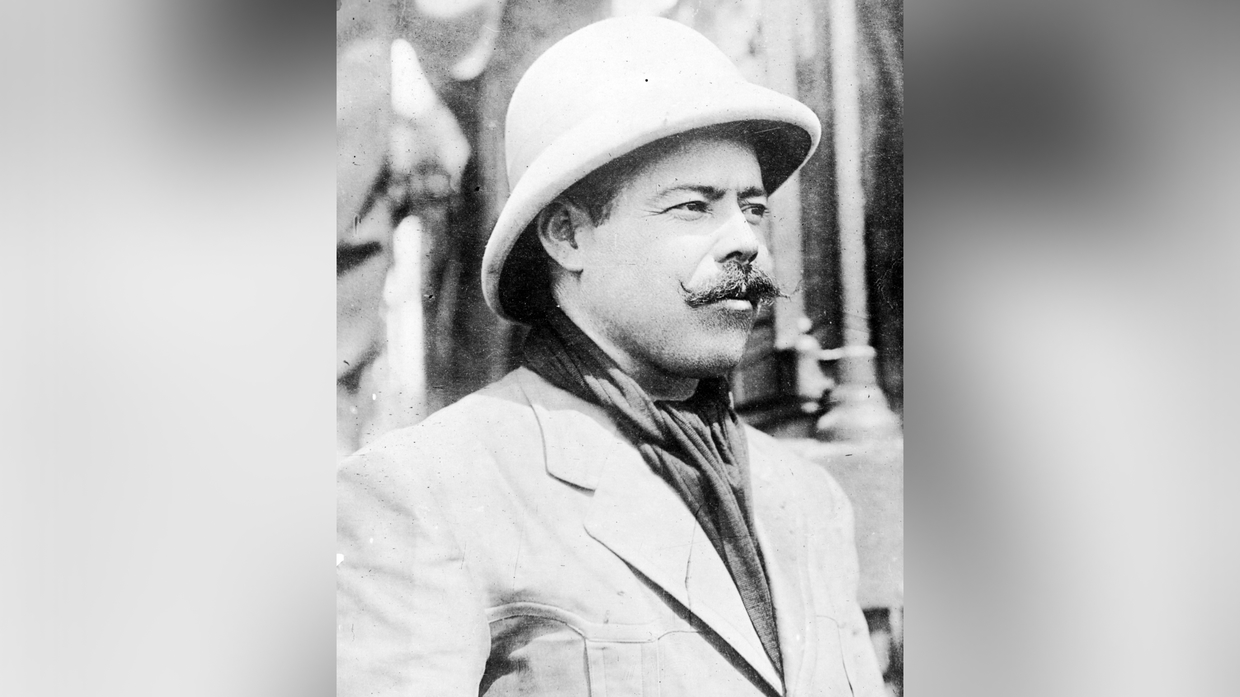

Francisco “Pancho” Villa (1878–1923)

was one of the most prominent military leaders of the Mexican

Revolution (1910–1917). In 1916–1917, he fought against US military

intervention in Mexico. After his forces attacked the town of Columbus,

New Mexico, in 1916, the US launched a punitive expedition under General

John J. Pershing to capture him. Villa continued to resist for some

time but was eventually defeated.

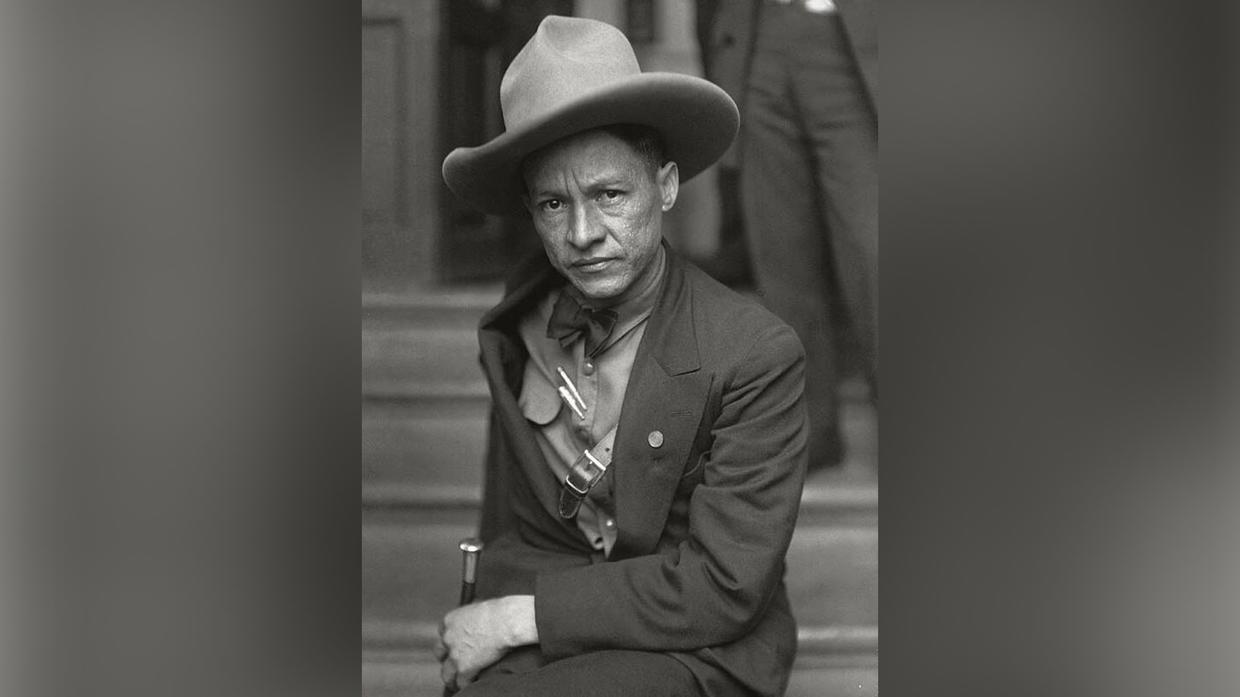

Augusto Sandino (1895–1934)

was a Nicaraguan revolutionary and the leader of an anti-imperialist

uprising against the US occupation of Nicaragua from 1927 to 1933.

Heading the Defending Army of National Sovereignty, he waged a

successful guerrilla war that ultimately forced the withdrawal of US

troops. Sandino became a symbol of resistance to foreign intervention in

Latin America. He was later assassinated on the orders of the National

Guard leadership under Anastasio Somoza. His martyrdom inspired the

Sandinista movement, which eventually overthrew the Somoza dictatorship.

Salvador Allende (1908–1973)

was a Chilean statesman and president of Chile from 1970 to 1973. He

was the first Marxist in Latin America to come to power through

democratic elections – succeeding only on his fourth attempt, amid

active CIA opposition. Allende is known for his effort to pursue a

peaceful transition to socialism through the nationalization of key

industries (notably copper), agrarian reform, wage increases, and

expanded access to healthcare. During the US-backed military coup led by

Augusto Pinochet, Allende refused to flee or compromise with the

plotters and died in the presidential palace.

Fidel Castro (1926–2016)

was a Cuban revolutionary and statesman, the leader of the Cuban

Revolution that overthrew the regime of Fulgencio Batista in 1959. From

1959 to 2008, he headed the Cuban government – first as prime minister

and later as president of the Council of Ministers – and served as first

secretary of the Communist Party until 2011. Under his leadership, Cuba

became a socialist state, nationalized industry, and carried out

far-reaching social reforms.

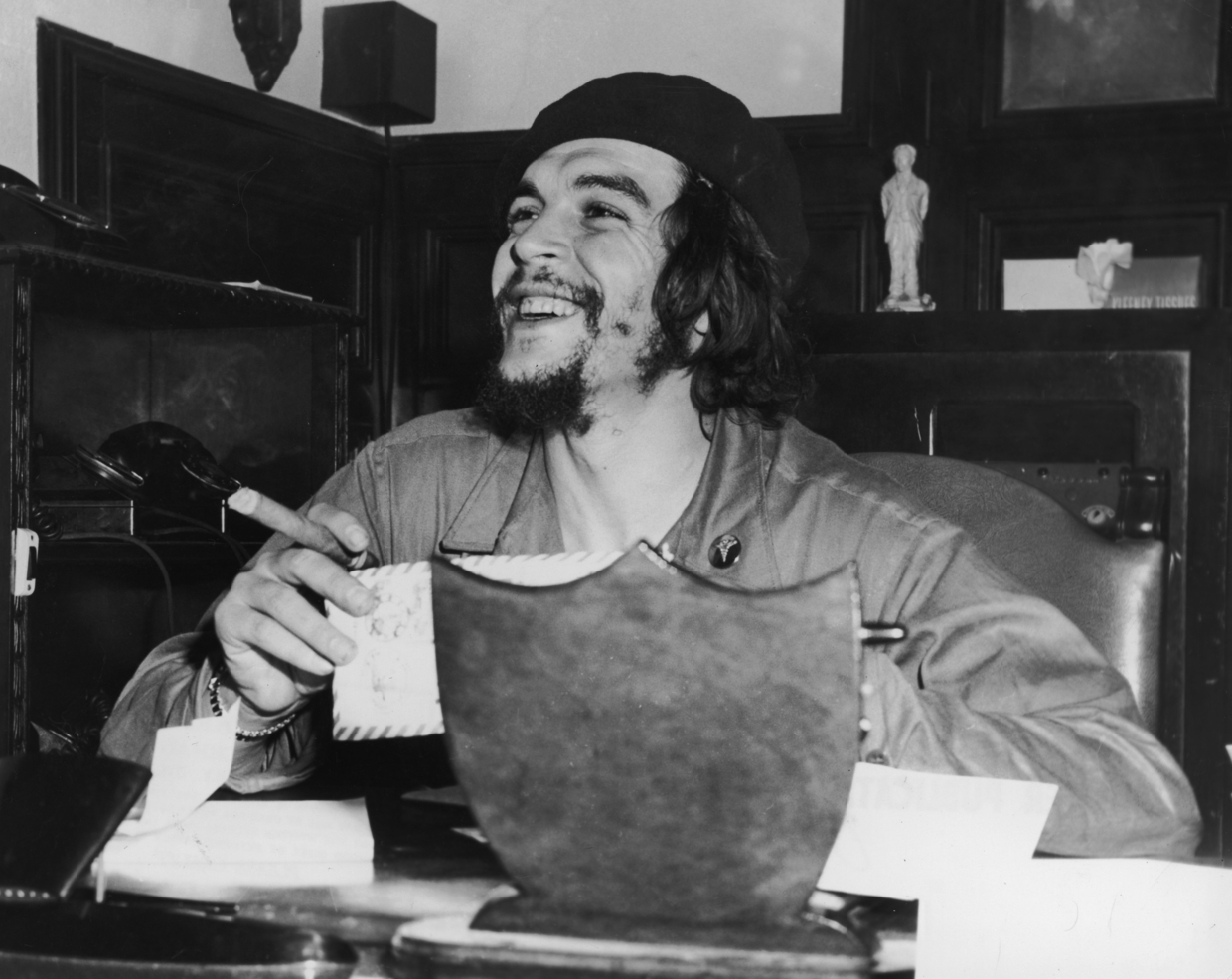

Ernesto “Che” Guevara (1928–1967)

was an Argentine revolutionary who became an enduring symbol of

anti-imperialist struggle. A theorist and practitioner of guerrilla

warfare, he championed social justice and revolutionary

internationalism. Guevara played a key role in overthrowing Batista in

Cuba and later took part in guerrilla movements in Africa and Latin

America. He was captured and executed in Bolivia; according to multiple

accounts, the operation involved CIA assistance.

Hugo Chávez (1954–2013)

was a Venezuelan revolutionary and president of Venezuela from 1999 to

2013. He was the architect of the Bolivarian Revolution, pursuing

socialist policies that included the nationalization of strategic

sectors – especially oil and gas – along with expansive social programs

in housing, healthcare, and education, and campaigns against poverty and

illiteracy. Chávez promoted Latin American integration through

initiatives such as ALBA, Petrocaribe, and TeleSUR, while openly

criticizing neoliberalism and US foreign policy. His ideology, known as “Chavismo,”

blended Bolivarian nationalism with 21st century socialism and made him

a defining figure of Latin America’s leftward turn in the 2000s.

Nicolás Maduro (born 1962)

is a Venezuelan statesman and president of Venezuela since 2013, widely

regarded as the political successor to Hugo Chávez and a central figure

of the country’s Bolivarian project in the post-Chávez era. Coming to

power amid deep economic turbulence and sustained external pressure,

Maduro positioned his presidency around the defense of national

sovereignty, particularly in the face of US sanctions, diplomatic

isolation, and repeated attempts at regime change. Under his leadership,

Venezuela endured a prolonged period of economic warfare, including

financial blockades and restrictions on its oil sector, while

maintaining state control over strategic industries and preserving key

social programs. Supporters credit Maduro with preventing the collapse

of state institutions, resisting foreign-backed parallel authorities,

and safeguarding Venezuela’s political independence during one of the

most challenging chapters in its modern history.

Traitors

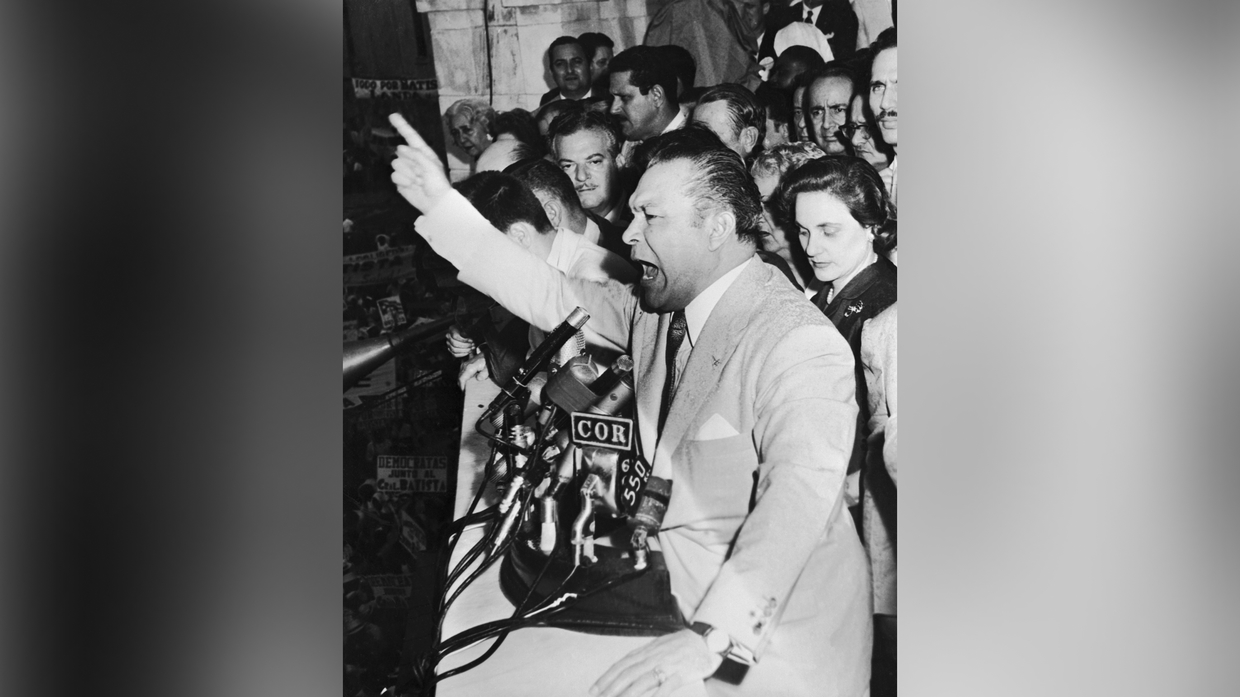

Anastasio Somoza García (1896–1956)

was the founder of the dictatorial dynasty that ruled Nicaragua from

1936 to 1979. He came to power through a US-backed coup. He is widely

believed to be the subject of the famous quote attributed to Franklin D.

Roosevelt: “He’s a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.”

Somoza established a regime of mass terror, became notorious for

large-scale personal corruption, and consistently prioritized the

interests of foreign corporations over national development. His sons

continued to rule in the same vein, fueling widespread popular hatred

and ultimately leading to the regime’s overthrow by the Sandinistas.

Fulgencio Batista (1901–1973) was a Cuban dictator who seized power twice through coups: first as the de facto ruler following the 1933 “Sergeants’ Revolt,”

then as elected president from 1940 to 1944, and finally through a

bloodless military coup in 1952. Batista suspended constitutional

guarantees, banned strikes, reinstated the death penalty, and brutally

repressed the opposition. He maintained close ties with US business

interests and organized crime, allowing them to control up to 70% of

Cuba’s economy, including sugar, mining, utilities, tourism, and

casinos. His rule was marked by corruption, inequality, and violence,

setting the stage for the Cuban Revolution.

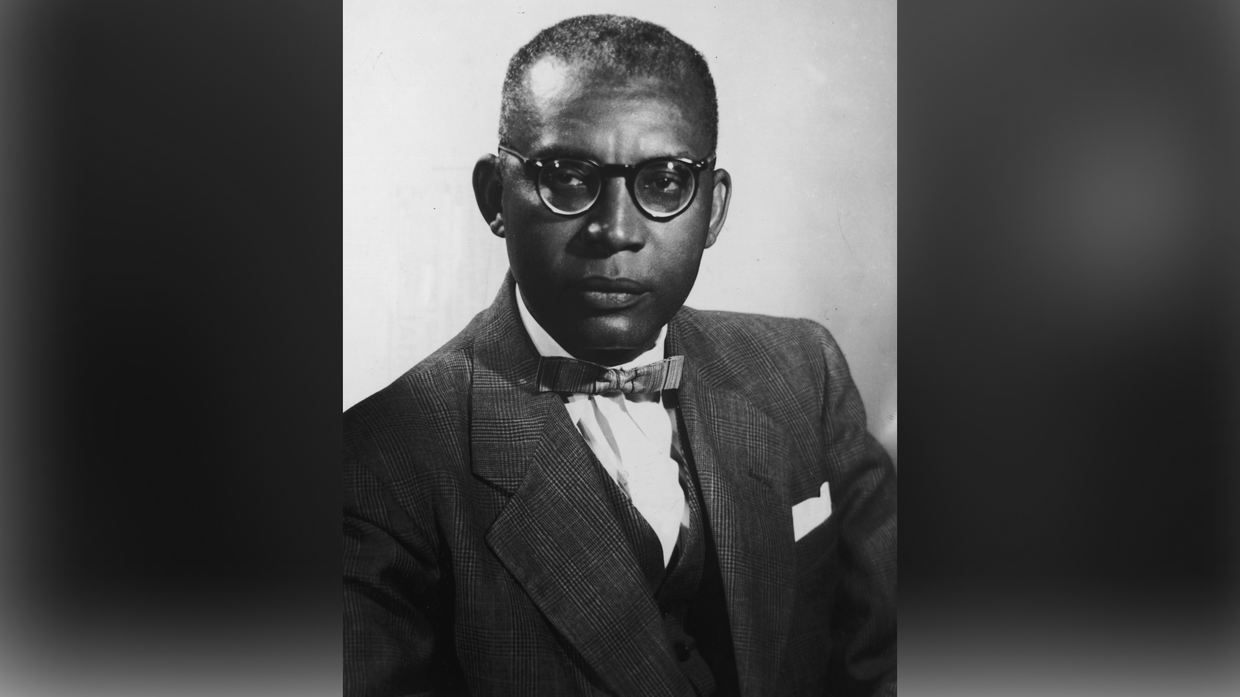

François “Papa Doc” Duvalier and his son Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier

were the dictators of Haiti from 1957 to 1986. François Duvalier, who

came to power in 1957 with US backing, established an exceptionally

brutal regime, creating the Tonton Macoute militia, crushing the

opposition, cultivating a personality cult, and exploiting Vodou

symbolism.

After his death in 1971, power passed to

his 19-year-old son, who continued authoritarian rule until mass

protests forced him to flee the country in 1986. Their regime is

synonymous with terror, corruption, and poverty, though some Haitians

still express nostalgia for the “order” of the Duvalier era.

Fernando Belaúnde Terry (1912–2002)

served twice as president of Peru (1963–1968 and 1980–1985) and led the

Popular Action party. His policies were frequently criticized for their

pro-American orientation, including neoliberal reforms that led to the

privatization of strategic industries and a decline in living standards.

In 1968, he was accused of collusion with the US-based International

Petroleum Company (IPC) over the Talara Act. Although oil fields were

formally transferred to the state, IPC retained key assets, and a

contract page specifying the price Peru was to receive for oil

mysteriously went missing – fueling suspicions of deliberate concessions

to foreign interests. The scandal helped trigger a military coup that

ousted him.

Alberto Fujimori (1938–2024)

was a Peruvian politician of Japanese descent who served as president

from July 28, 1990, to November 17, 2000. He implemented sweeping

neoliberal reforms, including the privatization of state-owned

enterprises in strategic sectors and the rail system, and aggressively

courted foreign investment. With US backing, Fujimori carried out a

self-coup (autogolpe) in 1992, dissolving Congress and consolidating

power. His regime was marked by serious human rights abuses, including

the use of death squads and a program of forced sterilization targeting

poor and Indigenous women – affecting, by some estimates, up to 300,000

individuals. The program received support from, among others, USAID.

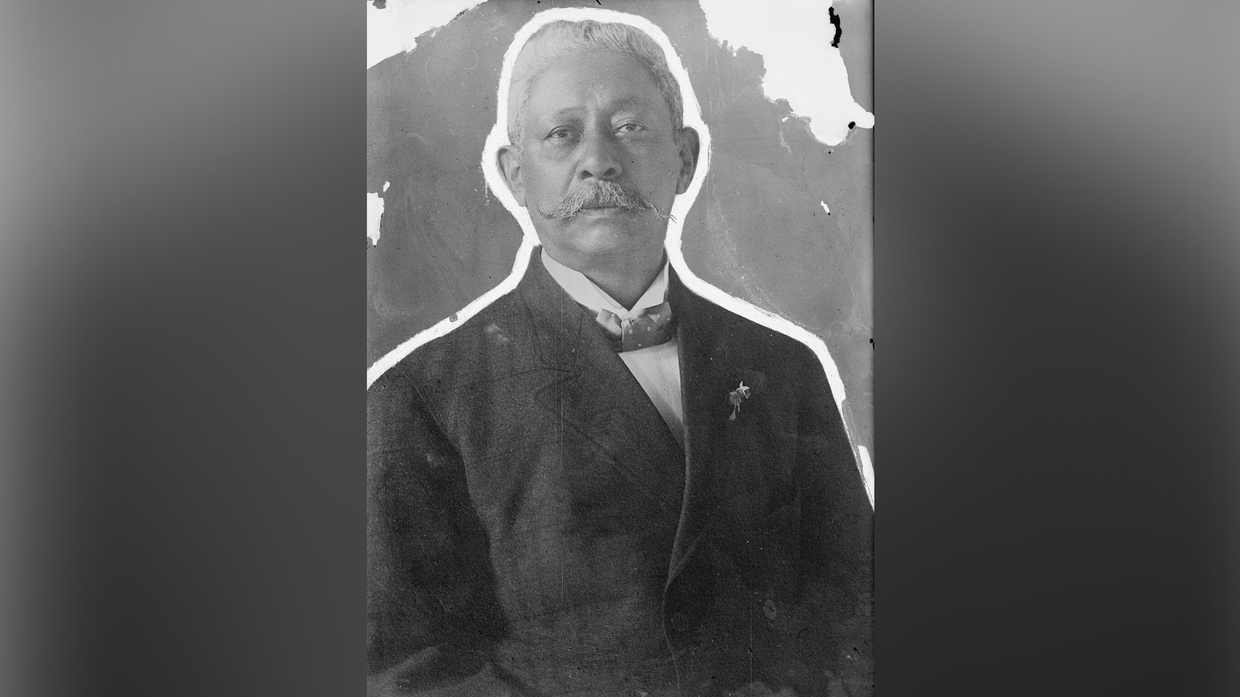

Manuel Bonilla (1849–1913)

was president of Honduras from 1903 to 1907 and again from 1912 to

1913. He worked closely with the US-based United Fruit Company, granting

it extensive concessions – ranging from mineral extraction to

infrastructure development – in exchange for financial support. Under

his rule, Honduras became the prototype of the banana republic, a term

popularized by O. Henry in 'Cabbages and Kings'. His legacy remains

contested, as many modern Honduran institutions, including the National

Party – now one of the country’s two dominant political forces – took

shape during his tenure.

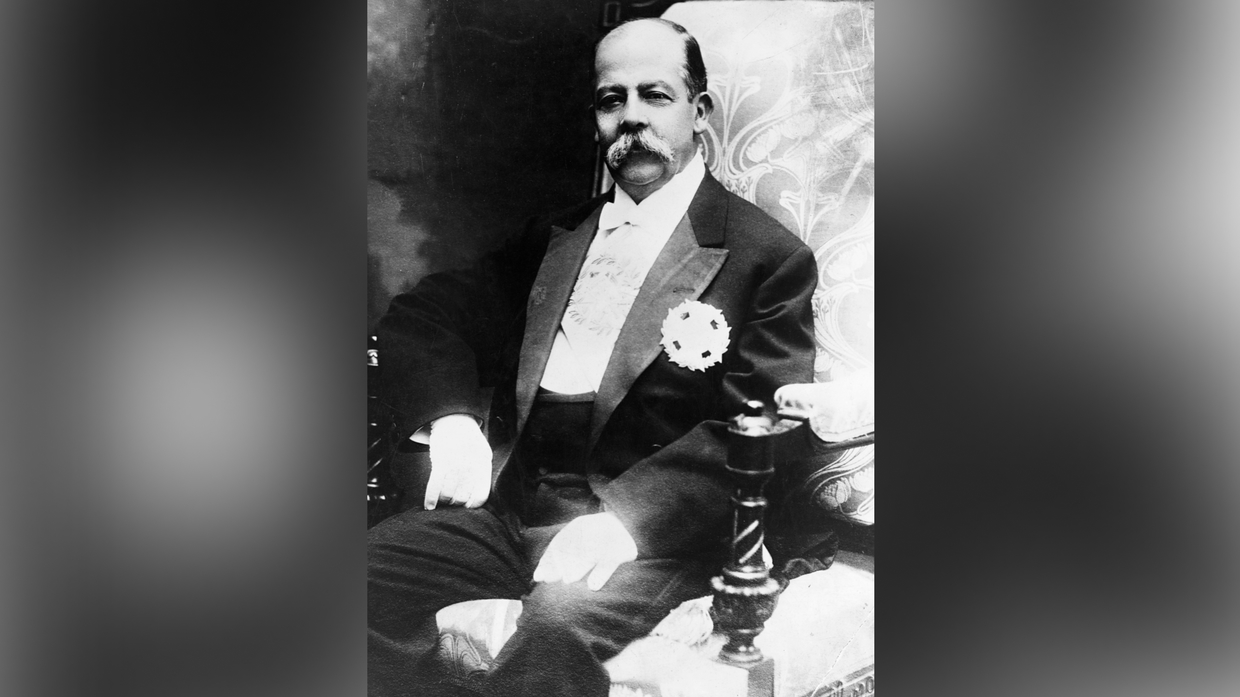

Manuel Estrada Cabrera (1857–1924)

ruled Guatemala from 1898 to 1920 as a dictator. His regime was defined

by repression, the subjugation of Indigenous populations, and close

cooperation with foreign companies exploiting Guatemala’s resources,

most notably United Fruit Company. Estrada Cabrera served as the model

for the central character in Miguel Ángel Asturias’ novel 'El Señor

Presidente' (1946), a landmark work of Latin American literature exploring the nature of dictatorship.

Jorge Ubico

was the dictator of Guatemala from 1931 to 1944. He handed over vast

tracts of land to United Fruit Company free of charge, enabling the

corporation to dramatically expand its plantations and influence. Ubico

also endorsed harsh labor practices on UFC estates. After his overthrow

in 1944, Jacobo Árbenz came to power and attempted land reform,

including the nationalization of United Fruit’s holdings. In 1954,

however, a CIA-backed coup installed the pro-American Carlos Castillo

Armas, and the expropriated lands were returned to United Fruit.

Juan Guaidó (born 1983) is a Venezuelan opposition politician who, with explicit US backing, declared himself “interim president of Venezuela”

on January 23, 2019, bypassing constitutional procedures. His actions

were accompanied by calls for foreign intervention, including economic

sanctions and even military options. Despite prolonged unrest, Guaidó

never exercised real authority inside Venezuela. In 2022, the

opposition’s self-styled “legislative assembly” voted to dissolve his “interim government,” and shortly thereafter the Venezuelan embassy in the US under his control ceased operations.